Most authors can trace back the source of their writing passion to a very special moment or person from their youth, and according Dr. Bunmi Oyinsan, world-renowned author and African culture thought-leader, her impressive body of work was inspired by the female heroines of her maternal grandmother’s stories.

“My grandmother’s stories always depicted women as strong and valiant, and she also told stories about Dahomean women warriors,” Dr. Bunmi said. “Most of the literature I was made to read in school were by men and I found the women in these narratives were quite different from those in my grandmother told. So, I was eager to write stories that would celebrate the powerful and inspiring women from my grandmother’s tales.”

Trying to close the cognitive dissonance between the heroines of her grandmother’s tales to the often invisible women of the African literature she was surrounded with, Dr. Bunmi set out to write about real and inspiring African heroines. “Most of my works have developed in response not only to the flat, negative, and often invisible portrayal of African women in some novels but also as a result of the recognition that ours is still predominantly oral culture… In addition to being inspired by works of other women writers, I situate myself firmly within the traditions of women story tellers.”

We sat down with Dr. Bunmi Oyinsan to discuss her literary roots, the importance of placing women at the centre of story-telling, and her latest book ‘Three Women.’ Commenting on her latest novel, Dr. Bunmi says, “My novel Three Women has been about claiming a voice or voices for women as the case may be, by creating female characters from a woman’s perspective… I also believe that it is important to show women not only as victims, but as active determinants of the course of their lives as well as active elements in their communities.”

We also talk about her philanthropic work with ‘Lekki Affordable Schools’ in Nigeria, how the concept of ‘Sankofa’ informs her writing and why celebrating African voices amid the context of the Black Lives Matter movement, is more important than ever.

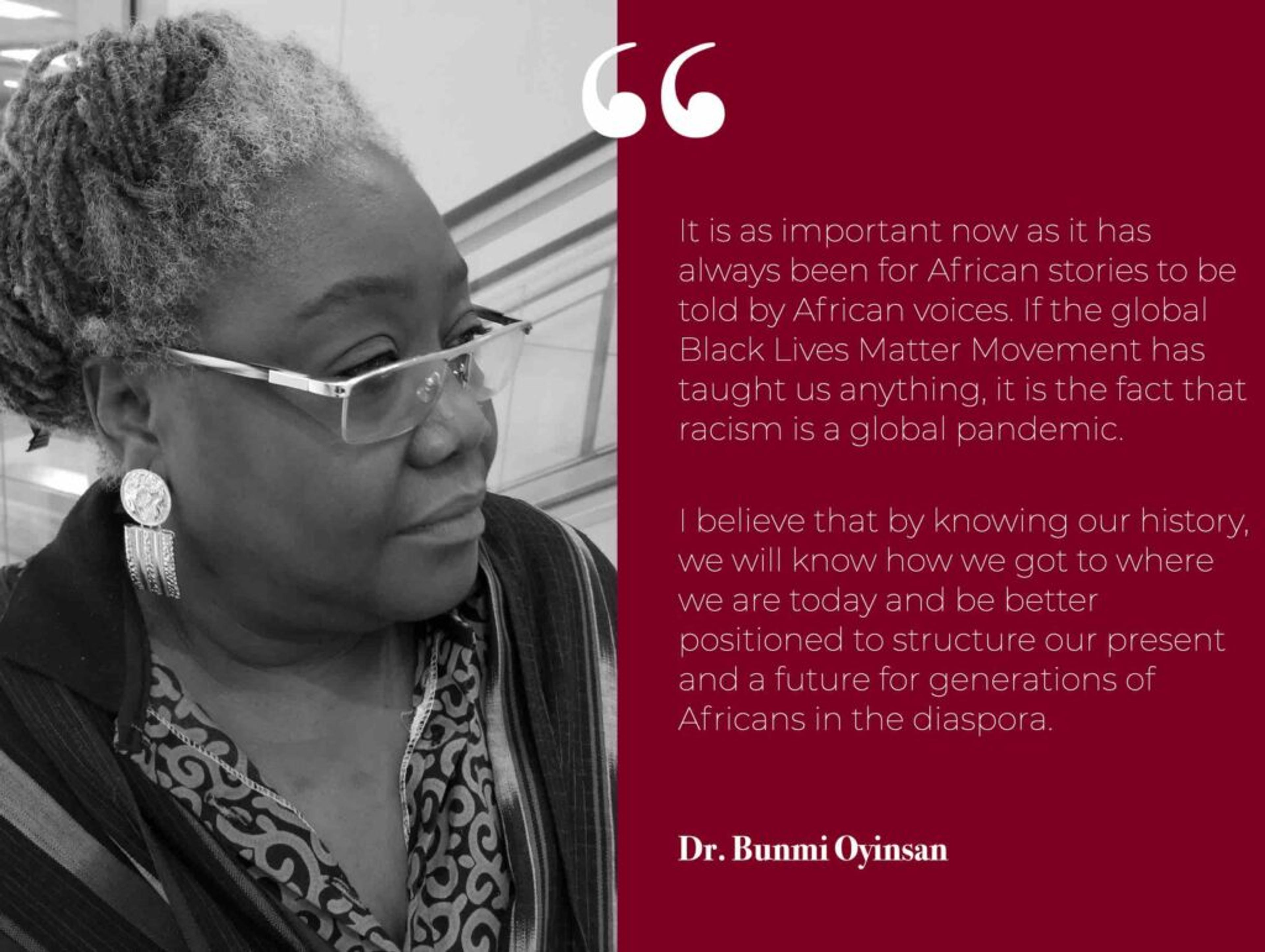

“It is as important now as it has always been for African stories to be told by African voices. If the global Black Lives Matter Movement has taught us anything, it is the fact that racism is a global pandemic,” Bunmi says. “At any given time, there seems to be only room for a few writers of colour and the big prizes and publishers who are not people of colour are the ones who determine whose voices get heard. We need to change this.”

Dr. Bunmi Oyinsan

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your background?

I was born in Lagos but spent my formative years in Port Harcourt. I started my post-secondary education in the UK and then studied for my masters and doctorate in Canada, where I now live. I started writing as a teenager. I was inspired by the stories that my maternal grandmother told me when I was growing up. Sometimes she told traditional stories, but she also made up her own stories to keep me entertained.

Her stories always depicted women as strong and valiant (her family had migrated to Lagos from Dahomey, now Republic of Benin) and she also told stories about Dahomean women warriors. Sometimes her stories were about real women, her contemporaries like Mrs. Funmilayo Ransome Kuti and Sisi Obasa (Mrs. Charlotte Obasa) to name a few. Unfortunately, most of the literature I was made to read in school were by men and I found the women in these narratives were quite different from the women in the stories my grandmother told me. So, I was eager to write stories that would celebrate the powerful and inspiring women from my grandmother’s stories.

What inspired you to seek out your current career path and eventually become a thought-leader for African culture?

I started the Sankofa Pan African Series because I’ve always loved history. I have many fond memories from my earliest history lessons about the great African civilizations and historical figures, like Mansa Musa, Emmanuel Aggreh, Jaja of Opobo, Nana of Itsekiri to mention just a few.

Although, I must confess that because my maternal grandmother who as I said earlier regaled me with stories about women, I quickly figured out that the history I was being taught at school was incomplete because there were hardly any women in them!

This foundation made me question, even more, the history I was taught in secondary school, which while purporting to be world history was mostly European history. My children’s generation was worse off because they were not taught African history in primary school like I was, despite the fact that they attended primary school in Nigeria. Another reason why I started the Sankofa Pan African Series is because it is, of course, important for the future of Africans and Africans in diaspora to have as many voices emphasizing the fact that civilization did not originate in European countries as most of the history books out there try to lead us to believe. Neither does civilization end in the countries that now represent the so-called developed world.

Tell us more about your latest book for adults ‘Three Women’ as well as your latest children’s books?

Three Women is my latest novel for adults. I have, since the release of Three Women, published four illustrated children’s story books. These children’s illustrated books come in two different series: The Legends of Africa Series, which introduces children to the stories of noteworthy Africans and people of African descent who have made a significant impact in the world. Currently, the series has two books: Mansa Musa: The Richest Man Who Ever Lived and Phillis Wheatley: The Girl Who Wrote Her Way to Freedom.

The Second Series is the Adventures of Anansi And Sewa. The first book in that series is Rainy Day and the second one is The Missing Black Panther. With the Anansi and Sewa Series, I am introducing the beloved trickster figure in many African and Caribbean stories, Anansi to children of this age who might not necessarily find a lot in common with the traditional folktales that my generation and others grew up with. So, the Anansi in my stories is a young Spider boy who sometimes gets into scraps with his sister Sewa. We see them as anthropomorphised creatures interacting with other members of the Spider family.

What is Three Women all about? How has your own personal history influenced your writing?

My work for adults, including my novel Three Women, is about claiming a voice or voices for women as the case may be, by creating female characters from a woman’s perspective. Most of my books, stage plays, and films have had female protagonists. I have found myself reacting to orature because of the role which story-telling played in my choice of vocation. In addition to being inspired by works of other women writers, I situate myself firmly within the traditions of women story tellers.

Most of my works have developed in response not only to the flat, negative, and often invisible portrayal of African women in some novels but also as a result of the recognition that ours is still predominantly oral culture. Although the temptation initially was to create only ‘perfect’ characters, I have tried to acknowledge — where a female character has flaws — that I focus on the causes of such flaws rather than to propagate the assumption that women are naturally weak, evil or devious. I also believe that it is important to show women not only as victims, but as active determinants of the course of their lives as well as active elements in their communities.

My interest in orature is also illustrated by the fact that when I sit down to write, I find myself responding to several stimuli. Sometimes it is the lyrics of a song, a particular proverb, the strands of a conversation I have heard somewhere, something I read or saw in a stage play or on the television which plays at the back of my mind. It was also in a bid to interact with the various elements with which I was determined to create a dialogue that I ventured into film-making.

Your prolific literary works have helped put African stories on a global stage. In your opinion, how important is it that African voices be heard in the context of 2021?

It is as important now as it has always been for African stories to be told by African voices. If the global Black Lives Matter Movement has taught us anything, it is the fact that racism is a global pandemic. Its manifestation might be different, but it is not restricted to the borders of individual countries. Racism is at the bottom of the way in which a continent as rich as Africa is, is also the poorest continent. Yes, most African leaders are corrupt, but corruption is not the only culprit responsible for the situation of Africa.

What is responsible for the warped global economic structure which ensures that African countries are not in control of their natural resources? African farmers can continue to slave from now till kingdom come and if they cannot determine the prices of their produce, they will remain poor. African voices must continue to be raised in any way Africans can to denounce the continued pillaging of the continent and the continued oppression of people of African descent all over the world.

Your written works are known to embrace the concept of ‘Sankofa’ could you tell us more about this?

The word Sankofa comes from Ghana. An Adinkra symbol for Sankofa represents it as a mythical bird flying forward with its head turned backwards. For many years, I used to wear a bronze bracelet with this symbol on it. The bird depicted in my bracelet had an egg in its mouth which I was told represents gems of knowledge available in the past. The bird on my bracelet held an egg in its beak and was poised as if ready to take flight forward. I know that there could be several interpretations for this, but my favourite is that the bird takes from the past useful knowledge which helps it to build a positive present thereby laying a solid foundation for future generations.

In the same vein, I believe that by knowing our history, we will know how we got to where we are today and be better positioned to structure our present and a future for generations of Africans in the diaspora. As such, the Sankofa Pan African Series explores African experiences and the realities of a global relationship from a variety of viewpoints. We look at transnational territories – and possible territory that might exist for a new generation of Africans and Africans in diaspora.

Outside of your work as an author, you have also dedicated your life to supporting a number of non-profit organisations with a special focus on those that support children’s rights, women’s rights and economic empowerment. Tell us more about your philanthropic work. Could you elaborate on what has been the most fulfilling milestone so far?

I am really pleased with the modest contribution that I have made towards Nigerian education through our schools. I co-founded Lekki Peninsula College in Lagos, after Maroko was demolished under a military government. I had no interest of running a school, but I saw too many teenagers who had dropped out of the system, who I knew would have a brighter future if only they had the opportunity to get a proper education. We set up the Lekki Peninsula Nursery and Primary School a sister school when we realised that we were doing too much remedial work with students that were going into the secondary school. We wanted to intervene earlier. Collectively, the two schools are known in the Lekki area as Lekki Affordable Schools. We also set up Equality Through Education Foundation (ETEF) to raise scholarships and other kinds of support for children and youths.

As a woman of colour, what has been the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome in your career?

As a woman of colour and as an author, the greatest challenge has been contending with the issue of access to publication. Very few publishers and even literary agents are interested in taking on writers of colour especially women. The problem with accessing publication is no different to the challenges that actors and other artists of colour face. At any given time, there seems to be only room for a few writers of colour and the big prizes and publishers who are not people of colour are the ones who determine whose voices get heard. We need to change this.

Comments are closed.